|

|

|

|

The Nobel Peace Prize 1901

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Jean Henri Dunant

|

Frédéric Passy

|

1/2 of the prize 1/2 of the prize

|

1/2 of the prize 1/2 of the prize

|

|

Switzerland |

France |

| |

|

|

Founder of the

International Committee of the Red Cross, Geneva; Originator Geneva

Convention (Convention de Genève) |

Founder and President of

first French peace society (since 1889 called Société française pour

l'arbitrage entre nations) |

b. 1828

d. 1910 |

b. 1822

d. 1912 |

The Nobel Peace Prize 1901

The Occasion of the First Award

The first Nobel Peace Prize was awarded at a meeting of

the Norwegian Parliament which took place at ten o'clock on the morning of

December 10, 1901. The ceremony was brief, lasting only fifteen minutes. Mr.

Carl Christian Bemer, president of the Parliament, opened it with this brief

address*:

"The Norwegian people have always demanded that their

independence be respected. They have always been ready to defend it. But, at

the same time, they have always had a keen desire and need for peace. Our

nation has wished to pursue its material and intellectual development in

peace and on good terms with other nations. This basic concept has been put

into practice repeatedly and with increasing strength by the Norwegian

Parliament. At various times the Parliament has gone on record in favor of

the signing of peace and arbitration treaties with foreign powers in order

to prevent settlement of possible disputes by armed force and to insure just

solutions through peaceful means. We may well believe that this need which

motivates the Norwegian people, this ardent desire for peace and good

relations between nations, is what influenced Dr. Alfred Nobel to entrust to

the Parliament of Norway the important responsibility of awarding the prize,

through a committee of five, to the one whose work for peace and for

fraternity among nations most deserves it. Today when this Peace Prize is to

be awarded for the first time, our thoughts turn back in respectful

recognition to the man of noble sentiments who, perceiving things to come,

knew how to give priority to the great problems of civilization, putting in

first place among them work for peace and fraternity among nations. We hope

that what he has done in the interest of this great cause will achieve

results which will live up to his noble intentions."

Upon completing his remarks, Mr. Bemer gave the floor

to Mr. Jorgen Gunnarsson Løvland, a member of the Nobel Committee and at

this time minister of Public Works. Mr. Løvland, in place of Mr. Getz, the

Committee chairman, who had died the previous month, announced that the

prize was awarded half to Henri Dunant and half to Frederic Passy. There was

no presentation speech, and after some further official formalities, the

Parliament adjourned.

Les Prix Nobel does not record that either of the laureates was

present; and neither delivered a Nobel lecture later, each, at his own

request, having been released from this obligation by the Nobel Committee.

* The translation is based on the Norwegian text in

Les Prix Nobel en 1901, which also contains a French translation.

From Nobel Lectures, Peace 1901-1925, Editor

Frederick W. Haberman, Elsevier Publishing Company, Amsterdam, 1972

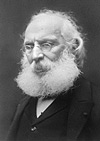

Henri Dunant – Biography

Jean

Henri Dunant's life (May 8, 1828-October 30, 1910) is a study in

contrasts. He was born into a wealthy home but died in a hospice; in middle

age he juxtaposed great fame with total obscurity, and success in business

with bankruptcy; in old age he was virtually exiled from the Genevan society

of which he had once been an ornament and died in a lonely room, leaving a

bitter testament. His passionate humanitarianism was the one constant in his

life, and the

Red Cross his living monument. Jean

Henri Dunant's life (May 8, 1828-October 30, 1910) is a study in

contrasts. He was born into a wealthy home but died in a hospice; in middle

age he juxtaposed great fame with total obscurity, and success in business

with bankruptcy; in old age he was virtually exiled from the Genevan society

of which he had once been an ornament and died in a lonely room, leaving a

bitter testament. His passionate humanitarianism was the one constant in his

life, and the

Red Cross his living monument.

The Geneva household into which Henri Dunant was born was religious,

humanitarian, and civic-minded. In the first part of his life Dunant engaged

quite seriously in religious activities and for a while in full-time work as

a representative of the Young

Men's Christian Association, traveling in France, Belgium, and Holland.

When he was twenty-six, Dunant entered the business world as a

representative of the Compagnie genevoise des Colonies de Sétif in North

Africa and Sicily. In 1858 he published his first book, Notice sur la

Régence de Tunis [An Account of the Regency in Tunis], made up for the

most part of travel observations but containing a remarkable chapter, a long

one, which he published separately in 1863, entitled L'Esclavage chez les

musulmans et aux États-Unis d'Amérique [Slavery among the Mohammedans

and in the United States of America].

Having served his commercial apprenticeship, Dunant devised a daring

financial scheme, making himself president of the Financial and Industrial

Company of Mons-Gémila Mills in Algeria (eventually capitalized at

100,000,000 francs) to exploit a large tract of land. Needing water rights,

he resolved to take his plea directly to Emperor Napoleon III. Undeterred by

the fact that Napoleon was in the field directing the French armies who,

with the Italians, were striving to drive the Austrians out of Italy, Dunant

made his way to Napoleon's headquarters near the northern Italian town of

Solferino. He arrived there in time to witness, and to participate in the

aftermath of, one of the bloodiest battles of the nineteenth century. His

awareness and conscience honed, he published in 1862 a small book Un

Souvenir de Solférino [A Memory of Solferino], destined to make

him famous.

A Memory has three themes. The first is that of the battle itself.

The second depicts the battlefield after the fighting - its «chaotic

disorder, despair unspeakable, and misery of every kind» - and tells the

main story of the effort to care for the wounded in the small town of

Castiglione. The third theme is a plan. The nations of the world should form

relief societies to provide care for the wartime wounded; each society

should be sponsored by a governing board composed of the nation's leading

figures, should appeal to everyone to volunteer, should train these

volunteers to aid the wounded on the battlefield and to care for them later

until they recovered. On February 7, 1863, the Société genevoise d'utilité

publique [Geneva Society for Public Welfare] appointed a committee of five,

including Dunant, to examine the possibility of putting this plan into

action. With its call for an international conference, this committee, in

effect, founded the Red Cross. Dunant, pouring his money and time into the

cause, traveled over most of Europe obtaining promises from governments to

send representatives. The conference, held from October 26 to 29, with

thirty-nine delegates from sixteen nations attending, approved some sweeping

resolutions and laid the groundwork for a gathering of plenipotentiaries. On

August 22, 1864, twelve nations signed an international treaty, commonly

known as the Geneva Convention, agreeing to guarantee neutrality to sanitary

personnel, to expedite supplies for their use, and to adopt a special

identifying emblem - in virtually all instances a red cross on a field of

white1.

Dunant had transformed a personal idea into an international treaty. But his

work was not finished. He approved the efforts to extend the scope of the

Red Cross to cover naval personnel in wartime, and in peacetime to alleviate

the hardships caused by natural catastrophes. In 1866 he wrote a brochure

called the Universal and International Society for the Revival of the

Orient, setting forth a plan to create a neutral colony in Palestine. In

1867 he produced a plan for a publishing venture called an «International

and Universal Library» to be composed of the great masterpieces of all time.

In 1872 he convened a conference to establish the «Alliance universelle de

l'ordre et de la civilisation» which was to consider the need for an

international convention on the handling of prisoners of war and for the

settling of international disputes by courts of arbitration rather than by

war.

The eight years from 1867 to 1875 proved to be a sharp contrast to those of

1859-1867. In 1867 Dunant was bankrupt. The water rights had not been

granted, the company had been mismanaged in North Africa, and Dunant himself

had been concentrating his attention on humanitarian pursuits, not on

business ventures. After the disaster, which involved many of his Geneva

friends, Dunant was no longer welcome in Genevan society. Within a few years

he was literally living at the level of the beggar. There were times, he

says2, when he dined on a crust of bread,

blackened his coat with ink, whitened his collar with chalk, slept out of

doors.

For the next twenty years, from 1875 to 1895, Dunant disappeared into

solitude. After brief stays in various places, he settled down in Heiden, a

small Swiss village. Here a village teacher named Wilhelm Sonderegger found

him in 1890 and informed the world that Dunant was alive, but the world took

little note. Because he was ill, Dunant was moved in 1892 to the hospice at

Heiden. And here, in Room 12, he spent the remaining eighteen years of his

life. Not, however, as an unknown. After 1895 when he was once more

rediscovered, the world heaped prizes and awards upon him.

Despite the prizes and the honors, Dunant did not move from Room 12. Upon

his death, there was no funeral ceremony, no mourners, no cortege. In

accordance with his wishes he was carried to his grave «like a dog»3.

Dunant had not spent any of the prize monies he had received. He bequeathed

some legacies to those who had cared for him in the village hospital,

endowed a «free bed» that was to be available to the sick among the poorest

people in the village, and left the remainder to philanthropic enterprises

in Norway and Switzerland.

| Selected Bibliography |

| Les Débuts de la Croix-Rouge en France.

Paris, Librairie Fischbacher, 1918. |

| Dunant, J. Henri. His manuscripts are held by the

Bibliothèque publique et universitaire de Genève. |

| Dunant, J. Henry, A Memory of Solferino.

London, Cassell, 1947. A translation from the French of the first

edition of Un Souvenir de Solférino, published in 1862. The

author published the original as «J. Henry Dunant», although he is

usually referred to as «Henri Dunant». |

| Gagnebin, Bernard, «Le Rôle d'Henry Dunant

pendant la guerre de 1870 et le siège de Paris», bound separately but

originally published in Revue internationale de la Croix-Rouge

(avril, 1953). |

| Gigon, Fernand, The Epic of the Red Cross or

the Knight Errant of Charity, translated from the French by Gerald

Griffin. London, Jarrolds, 1946. |

| Gumpert, Martin, Dunant: The Story of the Red

Cross. New York, Oxford University Press, 1938. |

| Hart, Ellen, Man Born to Live: Life and Work

of Henry Dunant, Founder of the Red Cross. London, Gollancz, 1953. |

| Hendtlass, Willy, «Henry Dunant: Leben und Werk»,

in Solferino, pp. 37-84. Essen Cityban, Schiller, 1959. |

| Hommage à Henry Dunant. Genève, 1963. |

| Huber, Max, «Henry Dunant», in Revue

internationale de la Croix-Rouge, 484 (avril, 1959) 167-173. A

translation of a brief sketch originally published in German in 1928. |

| |

1. The emblem in Muslim countries is the red crescent

and in Iran is the red lion and sun. (For a brief history of the Red Cross

see

history of the Red Cross.)

2. «Extraits des mémoires» in Les Débuts de la Croix-Rouge en France,

p. 72.

3. Taken from a letter written by Dunant and published by René Sonderegger;

quoted by Gigon in The Epic of the Red Cross, p. 147.

From Nobel Lectures, Peace 1901-1925, Editor

Frederick W. Haberman, Elsevier Publishing Company, Amsterdam, 1972

This autobiography/biography was

written at the time of the award and later published in the book series

Les Prix Nobel/Nobel

Lectures. The information is sometimes updated with an addendum

submitted by the Laureate. To cite this document, always state the source as

shown above.

Frédéric Passy – Biography

Frédéric Passy (May 20, 1822-June 12, 1912) was born in Paris and

lived there his entire life of ninety years. The tradition of the French

civil service was strong in Passy's family, his uncle, Hippolyte Passy

(1793-1880), rising to become a cabinet minister under both Louis Philippe

and Louis Napoleon. Educated as a lawyer, Frédéric Passy entered the civil

service at the age of twenty-two as an accountant in the State Council, but

left after three years to devote himself to systematic study of economics.

He emerged as a theoretical economist in 1857 with his Mélanges

économiques, a collection of essays he had published in the course of

his research, and he secured his scholarly reputation with a series of

lectures delivered in 1860-1861 at the University of Montpellier and later

published in two volumes under the title Leçons d'économie politique.

An admirer of Richard Cobden, he became an ardent free trader, believing

that free trade would draw nations together as partners in a common

enterprise, result in disarmament, and lead to the abandonment of war. Passy

lectured on economic subjects in virtually every city and university of any

consequence in France and continued a stream of publications on economic

subjects, some of the more important being Les Machines et leur influence

sur le développement de l'humanité (1866), Malthus et sa doctrine

(1868), L'Histoire du travail (1873). Passy's passionate belief in

education found expression in De la propriété intellectuelle (1859)

end La Démocratie et l'instruction (1864). For these contributions,

among others, he was elected in 1877 to membership in the Académie de

sciences morales et politiques, a unit of the Institut de France.

Frédéric Passy (May 20, 1822-June 12, 1912) was born in Paris and

lived there his entire life of ninety years. The tradition of the French

civil service was strong in Passy's family, his uncle, Hippolyte Passy

(1793-1880), rising to become a cabinet minister under both Louis Philippe

and Louis Napoleon. Educated as a lawyer, Frédéric Passy entered the civil

service at the age of twenty-two as an accountant in the State Council, but

left after three years to devote himself to systematic study of economics.

He emerged as a theoretical economist in 1857 with his Mélanges

économiques, a collection of essays he had published in the course of

his research, and he secured his scholarly reputation with a series of

lectures delivered in 1860-1861 at the University of Montpellier and later

published in two volumes under the title Leçons d'économie politique.

An admirer of Richard Cobden, he became an ardent free trader, believing

that free trade would draw nations together as partners in a common

enterprise, result in disarmament, and lead to the abandonment of war. Passy

lectured on economic subjects in virtually every city and university of any

consequence in France and continued a stream of publications on economic

subjects, some of the more important being Les Machines et leur influence

sur le développement de l'humanité (1866), Malthus et sa doctrine

(1868), L'Histoire du travail (1873). Passy's passionate belief in

education found expression in De la propriété intellectuelle (1859)

end La Démocratie et l'instruction (1864). For these contributions,

among others, he was elected in 1877 to membership in the Académie de

sciences morales et politiques, a unit of the Institut de France.

Passy was not, however, a cloistered scholar; he was a man of action. In

1867, encouraged by his leadership of public opinion in trying to avert

possible war between France and Prussia over the Luxembourg question, he

founded the «Ligue internationale et permanente de la paix». When the Ligue

became a casualty of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871, he reorganized it

under the title «Société française des amis de la paix» which in turn gave

way to the more specifically oriented «Société française pour l'arbitrage

entre nations», established in 1889.

Passy carried on his efforts within the government as well. He was elected

to the Chamber of Deputies in 1881, again in 1885, and defeated in 1889. In

the Chamber he supported legislation favorable to labor, especially an act

relating to industrial accidents, opposed the colonial policy of the

government, drafted a proposal for disarmament, and presented a resolution

calling for arbitration of international disputes.

His parliamentary interest in arbitration was whetted by

Randal Cremer's

success in guiding through the British Parliament a resolution stipulating

that England and the United States should refer to arbitration any disputes

between them not settled by the normal methods of diplomacy. In 1888 Cremer

headed a delegation of nine British members of Parliament who met in Paris

with a delegation of twenty-four French deputies, headed by Passy, to

discuss arbitration and to lay the groundwork for an organization to advance

its acceptance. The next year, fifty-six French parliamentarians,

twenty-eight British, and scattered representatives from the parliaments of

Italy, Spain, Denmark, Hungary, Belgium, and the United States formed the

Interparliamentary Union,

with Passy as one of its three presidents. The Union, still in existence,

established a headquarters to serve as a clearinghouse of ideas, and

encouraged the formation of informal individual national parliamentary

groups willing to support legislation leading to peace, especially through

arbitration.

Passy's thought and action had unity. International peace was the goal,

arbitration of disputes in international politics and free trade in goods

the means, the national units making up the Interparliamentary Union the

initiating agents, the people the sovereign constituency.

Through his prodigious labors over a period of half a century in the peace

movement, Passy became known as the «apostle of peace». He wrote unceasingly

and vividly. His Pour la paix (1909), which came out when he was

eighty-seven years old, is a personalized account - in lieu of an

autobiography which he deplored - of his work for international peace,

noting especially the founding of the Ligue, the «période décisive» when the

Interparliamentary Union was established, the development of peace

congresses, and the value of the Hague Conferences.

Passy was a renowned speaker, noted for the intellectual demands he made on

his audiences, as well as for his powerful voice, his ample gestures, and

his majestic and dignified manner.

| Selected Bibliography |

| «Frédéric Passy», American Journal of

International Law, 6 (October, 1912) 975-976. |

| Gide, Charles, «Obituary: Frédéric Passy

(1822-1912)», The Economic Journal, 22 (September, 1912) 506-507. |

| Institut international de bibliographie,

Répertoire bibliographique universel: Bibliographie des écrits de

Frédéric Passy. Bruxelles, 1900. |

| Le Foyer, Lucien, «Un Grand Pacifiste», Le

Monde illustré (29 juin 1912) 418. |

| Maza, Herbert, «Frédéric Passy: La Fondation de

l'Union Interparlementaire», in Neuf meneurs internationaux, pp.

223-239. Paris, 1965. |

| Obituary, Le Figaro (13 juin 1912) 2. |

| Obituary, the (London) Times (June 13,

1912) II. |

| Passy, Frédéric. The Passy M S S are in the

Library of the Peace Palace at The Hague. |

| Passy, Frédéric, «The Advance of the Peace

Movement throughout the World», American Monthly Review of Reviews,

17 (February, 1898) 183-188. An English translation of the original

article as it appeared in the Revue des revues. |

| Passy, Frédéric, La Démocratie et

l'instruction: Discours d'ouverture des cours publics de Nice.

Paris, Guillaumin, 1864. |

| Passy, Frédéric, Histoire du travail: Leçons

faites aux soirées littéraires de la Sorbonne. Paris, 1873. |

| Passy, Frédéric, Leçons d'économie politique.

Faites à Montpellier par M. F. Passy, 1860-1861. Recueillies par MM. E.

Bertin et P. Glaize. Montpellier, Gras, 1861. |

| Passy, Frédéric, Les Machines et leur

influence sur le développement de l'humanité. Paris , Hachette,

1866. |

| Passy, Frédéric, Mélanges économiques.

Paris, Guillaumin, 1857. |

| Passy, Frédéric, «Peace Movement in Europe»,

American Journal of Sociology, 2 (July, 1896) 1-12. |

| Passy, Frédéric, Pour la paix: Notes et

documents. Paris, Charpentier, 1909. |

| Passy, Frédéric, De la propriété

intellectuelle. Études par MM. F. Passy, V. Modeste, et P.

Paillottet. Paris, Guillaumin, 1859. |

| Passy, Frédéric, Sophismes et truismes.

Paris, Giard & Brière, 1910. |

| Van Schilfgaarde, Waszkléwicz, «Frédéric Passy»,

in Mannen en vrouwen van beteekenis in onze dagen. Haarlem,

Willink, 1900. |

From Nobel Lectures, Peace 1901-1925, Editor

Frederick W. Haberman, Elsevier Publishing Company, Amsterdam, 1972

This

autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and later

published in the book series

Les Prix Nobel/Nobel

Lectures. The information is sometimes updated with an addendum

submitted by the Laureate. To cite this document, always state the source as

shown above |

|

|